Ansel Adams said

You don’t take a photograph, you make it.

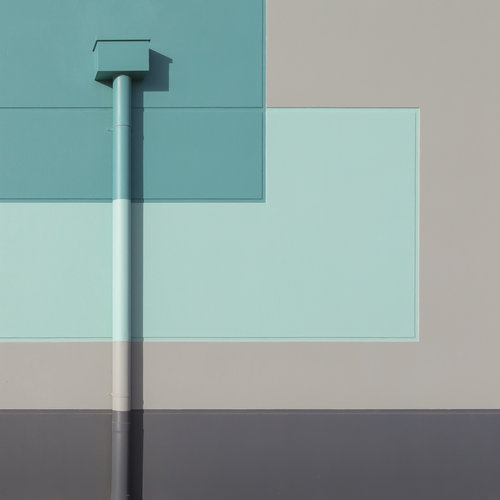

In Part 2 of ‘Talk about a picture’, Mark Brierleys award winning photography spells out the manner in which the artist manipulates the subject to achieve certain aesthetic ends. The artist casts his line with accuracy hooking the viewer to consider the images from alternate points of view. The two images discussed are favourites because the subtleties, intricacies and implicit messages are complex, and as a result they are at once moving and alluring. Having said that in this limited format only some aspects will be discussed.

Brierley feels

free to explore a vision for how he sees the world

Photography as art

____________________________________________

To say I am excited is a understatement!

Mark Brierley named Western Australian Commercial and Overall Professional Photographer of the Year 2019

Award winning photographer Mark Brierley is the recipient of the highest photographic accolades in the state of Western Australia for 2019. At the recent Australian Institute of Professional Photography annual awards in WA Brierley was named the 2019 Commercial Photographer of the Year and the Overall Professional Photographer of the Year.

Brierley was named overall winner at the 2019 AIPP Western Australian EPSON Professional Photography Awards

____________________________________________

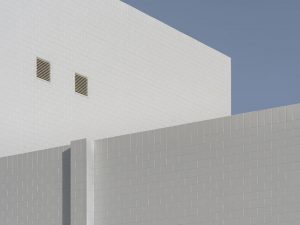

If we are going to build industrial centres, let’s at least ensure they are visually and environmentally appealing.

Whilst all works pictured are enigmatic for one reason or another, the picture I call Yellow wall with traffic cone is particularly so due not least to the obvious layers of history or ‘operational disruptions’ at once focusing and confusing our perception of it,

Furthermore, the artist is drawing attention to ‘hidden implications’ in this image. For example, what are the local government planning regulations relating to the design, size, alteration and aesthetics of industrial precincts? A point he has concerns about.

In Western Australia (the location of these images) the broader public must be consulted on such matters under the Local Government Act which is currently under review. Presumably this would enable the public to have a say regarding how their ‘neighbourhood’ projects to the broader community? Or are commercial sites built and altered by the owners within a modus operandi of relative indifference to the community’s opinion? For instance, the developers or owners may take the view, “It doesn’t matter what it looks like because we only make plastic ties inside”. Conversely, in spite of the Act requiring local government to consult broadly with the public, they may not receive many submissions; the public may be largely apathetic on these matters.

Yet, all local ‘renovations’ to existing buildings is connected in some way to the social history of the immediate area and thus to the State and Australia as a whole.

Sometimes superficially and in other cases profoundly. On a purely visual level this allows us to roughly identify when and why a building was built and what was important aesthetically at that point in time. And at a deeper level why buildings are preserved as social and historic records.

Sometimes superficially and in other cases profoundly. On a purely visual level this allows us to roughly identify when and why a building was built and what was important aesthetically at that point in time. And at a deeper level why buildings are preserved as social and historic records.

One of Brierley’s considerations is the oversight or lack of ‘visual integration’ industrial parks ‘should warrant’.

If a quick drive around industrial precincts, or industries located on the fringe of many Australian towns is anything to go by, planning departments within district government do not appear to place aesthetics high on the radar of industrial zoning. As a society, so much of what occurs within government seems to occur without factoring in the ‘broad aesthetic consequences’, or development is signed off without fully acknowledging future consequences.

Brierley says,

These urban environments are what fascinate me the most; how they are the support areas for residential zones, the speed at which they can be built and yet sometimes stay empty.

The biggest industrial area in the world The Tahoe Reno Industrial Center is a remarkable, massive 107,000 acre [433,013,637 square metres] park that encompasses a developable 30,000 acre industrial complex. It is located in Storey County, Nevada…

A couple of things.

If the Tahoe Reno Industrial Centre counts as progress and civilisation they come at a cost. Are industrial parks like Tahoe built sustainably; how much of what they process will end up in landfill? What are the environmental impacts: disruption to habitats of flora and fauna? The same questions arise in relation to containers in Part 1. Over 400,000,000 square metres must affect a lot of flora and fauna; not to mention geographical and geological disruption.

Implicit in Brierley’s ‘concern for the world around us’ is the recycling of existing buildings; reuse existing industrial stock and factories. Do we need to build new ones on the scale aforementioned, or should local government and commercial industry be working more closely with academia and urban and architectural planners to arrive at broader outcomes that serve not one purpose but a multitude of ‘community positive’ purposes?

Implicit in Brierley’s ‘concern for the world around us’ is the recycling of existing buildings; reuse existing industrial stock and factories. Do we need to build new ones on the scale aforementioned, or should local government and commercial industry be working more closely with academia and urban and architectural planners to arrive at broader outcomes that serve not one purpose but a multitude of ‘community positive’ purposes?

In spite of the myriad implications, the photographer is drawing attention to the fact that this is a picture; an artwork. He has focused on ‘a section of a single wall’ complete with various historic renovations and additions; decorative as well as operational.

Because this is an artwork and this part of the wall has been ‘chosen’, the visual and physical disruptions bring into play the concept of ‘figure and ground’ which centres on the notion of depth perception; both concepts are functions of certain abstract and figurative art.

Secondly, the image is derived from and embedded in the social and industrial fabric of an urban environment, with concomitant relations not dissimilar to that of containers outlined in Part 1.

The following is applicable as a starting point,

Figures constitute the objects we perceive and with which we interact. Therefore, figure assignment — the determination of which portions of the input correspond to figures — is a critical component of perception.

The above could be describing Yellow wall with traffic cone because of the infinite evidential references: there are innumerable ways to interpret this work and the others pictured here. Additionally, some aspects of the picture are more dominent than others.

While this image might inspire a ‘What is the subject of this picture’ question or, what drove the photographer to frame this particular part of this wall, these enquiries are not useful starting points, firstly because the image is a multi-faceted concept with wide-ranging connotations; incuding ‘disruptions’ to the conventional ‘figure and ground’ relationship. Disruptions not evident in a portrait, for example, in which the figure is ‘clearly’ the subject.

Secondly, ‘interpretation’ largely depends on the individual’s unique and diverse life experience. These ideas effectively eclipse neat questions of ‘why or what’ is the subject of this image.

All my images are left untitled so the viewer can form their own interpretation based on how they see and react to the image.

Images rarely mean ‘the same thing to disparate individuals.’ Kind of self-evident if we were to compare the reactions to yellow wall with traffic cone of an elderly man from a rural village in China with a Millenial studying anthropology in Melbourne.

In consequence there is no right or wrong way of interpreting an image, albeit visual information and context in communion with personal experience play a big part in propelling the viewer in certain directions.

It is impossible to ignore the evidence of ‘decorative and operational history’ the wall exhibits. The many and varied markings suggest adhoc changes across different time periods. There seems to be ongoing short term alterations which reveal a snapshot of local history (environmental and commercial/industrial) with immediate inferences.

So much of what we see here is ‘common imagery’, of a type largely accessible to anyone who lives in a city. The traffic cone invented in 1943 by American Charles Scanlon, is an object more associated with ‘civic’ use, nevertheless here it signals some kind of warning, and is an object as ubiquitous as the newspaper around the world.

The image concisely exposes the here-and-now linked at least to 1943 and all objects that have ‘changed the world’ under the radar.

Once more in the domain of the artwork, the viewer is propelled to consider the implications of the traffic cone in this and broader contexts.

Moreover, there is a feeling of visual balance in the demarcation of the picture into ‘rough thirds’ vertically and horizontally, although the horizontal is less pronounced, it is there nevertheless. The first third on the right-hand-side is decidedly different from the remaining two thirds on the left-hand side. There are competing visual hierarchies on the left side alone due to the superficial ‘maintenance disruptions’ as well as contending depth perceptions. Add to this the two sides competing with each other.

Starkly obvious is the ‘quiet order’ on the right in contrast to the ‘busy adhoc disorder’ on the left.

And yet they are united structurally and aesthetically in the projection of quadrilaterals showing the ‘original’ pale brick walls. The right quadrilateral composed and complete, the left quadrilateral, decomposing and incomplete. Interestingly the top row of both quadrilaterals equals 2.25 bricks, uncovering a subtle visual rapport between the two. Irrespective, they form part of the same wall.

What immediately comes to mind are the links to socialstructures and family machinations and hierarchies. Take children in a family, for example. One, single-minded, ordered and committed to following a set path, another, unsure of himself and his true calling, tries many different things at different times all of which leave residual impressions.

yellow wall with traffic cone can be interpreted as a description of social life: while we pretty much start off life in similar ways our journeys are a series of stops and starts, changing directions, beginnings and endings, rational versus spontaneous decisions – conscious and unconscious etc. These ideas are supported by the following in spite of forming part of the same wall (or construction at least)

yellow wall with traffic cone can be interpreted as a description of social life: while we pretty much start off life in similar ways our journeys are a series of stops and starts, changing directions, beginnings and endings, rational versus spontaneous decisions – conscious and unconscious etc. These ideas are supported by the following in spite of forming part of the same wall (or construction at least)

The two exposed brick quadrilaterals appear to be at different depths making the viewer flick continually between them in an attempt to work out how this could be.

They concisely encapsulate the fact that we are fundamentally the same when we begin life but our environment and the predominant sensibilities within our ‘encapsulated world’ can differ remarkably from person to person. There are many more incongruities all of which have complex ‘figure and ground’ disruptions at the heart and all of which can be explained socially.

There is further evidence of this concept in that the left-hand side has undergone obvious ‘transformations’, the frame is coming off the pale quadrilateral as well as falling apart; alternating paint colours suggest incremental activity. By contrast the ‘plastered wall’ contained in the right-hand third, has no ‘superficial’ markings, there is a sense that it is ‘complete, whole – finished’. Rational versus irrational, irrespective all decision making can be interpreted within broad values.

Overall, this is an image which contains ‘pictures within pictures within pictures’ and due to its elevation as ‘art’, we try and make sense of it, try to unravel the key to its existence based on our unique social experience. The fact that concepts compete for clarification means the image creates a stretched continuum between points of understanding or explanation and this makes it compelling as an artwork; much like green door with mop in Part 1.

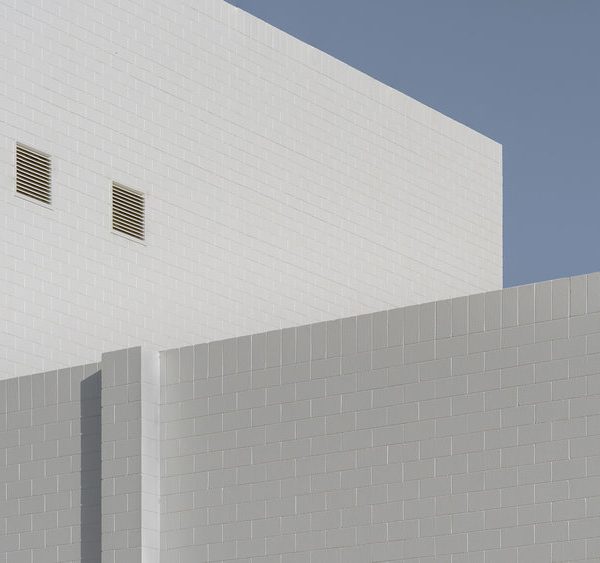

One more work in brief, white buildings. Like blue wall with traffic cone in Part 1, this work is moving in its graphic pristine simplicity, it forces us to contemplate expanses of achitecture within the natural world, whilst the chosen perspective, proclaims man’s dominance over the natural world. The perspective presents the monolithic lower wall pushing against the intermediary wall subsequently forcing the wedge of blue sky towards the picture plane and the viewer.

One more work in brief, white buildings. Like blue wall with traffic cone in Part 1, this work is moving in its graphic pristine simplicity, it forces us to contemplate expanses of achitecture within the natural world, whilst the chosen perspective, proclaims man’s dominance over the natural world. The perspective presents the monolithic lower wall pushing against the intermediary wall subsequently forcing the wedge of blue sky towards the picture plane and the viewer.

Moreover, the upper white building ‘seems to bleed into the lower wall’ by virtue of the light and angle the artist has chosen. In an ‘optical illusion’ the slim rectangular form drops down from the recessed building; at the same time visually, the perspective and light make the form appear further forward than the larger form from which it ‘appears to drop’.

These aspects together create an unresolvable tension in the viewer.

These aspects together create an unresolvable tension in the viewer.

The image is captivating because of the contrasts between what seems to be a straightforward picture of a building at first glance and what is a complex work perspectivally and formerly.

The impact of white buildings derives in part from a sense of the monumental buildings, on one hand, and the manipulation of light and perspective on the other.

As a work of art an interpretation challenge is set up for the viewer, between the image as it is in reality (noumenal) and the image as it is perceived by the senses (phenomenal); conceptual art versus the straight recording of a subject. A continuum exists between actual and manipulated environments. Or between photographic reality and imaginative unreality.

In spite of the fact that this work ‘appears simple’, it is at once complex, forceful, refined and restrained. With all that going on it is not surprising that it is consequently compelling.

“Thank you so much for the article Kim, an extremely thought provoking and insightful write up…Fantastic work and thanks again”

Mark Brierley