_____________________________

…‘junk art’ is primarily associated with the idiom of assemblage, a set of object based practices which emerged in the mid-1950s and culminated in the seminal exhibition The Art of Assemblage in New York in 1961.

_____________________________

Anyone who has first-hand knowledge of the desolate isolation and sense of loneliness that can grip souls in remote parts of Australia when things get tough due to drought (cattle dying, no planting, dams and turkey nests drying up, non-existent pasture) and a plethora of other issues will identify with many of Rosalie Gascoigne’s most important works.

As a young wife, Gascoigne came from Auckland to Mt Stromlo outside Canberra in 1943 aged 26 years; her husband Ben Gascoigne was an astronomer at the Mt Stromlo observatory. In a community where she knew few people, she spent much time alone raising three small children. With a lot of time on her hands, she immersed herself in the surrounding landscape and found solace in what she saw. After assimilating, Gascoigne identified with it and the desire to create something of herself from it.

______________________________________

Two of Gascoigne’s most moving works are Pink Window and Inland Sea and are particularly poignant in terms of the Australian outback.

Growing up on a cattle property in often drought-ridden west Queensland these works are particularly poignant. The symbolism is raw and immediate – desolation, drought, and little hope for improvement. For many Australian’s their outback experience reads similarly; especially the stories of early Australian women who accompanied their husbands to plots of land in the middle of nowhere in an attempt to etch out an existence. Female pioneers who until more recently were left out of the many narratives about Australian men who forged a life of sorts in the outback often against significant obstacles. Louisa Lawson’s (Henry Lawson’s mother) early life is a horrifying account of deprivation on every possible front in the last decades of the 19th century. The Durack family: Patrick (Patsy) Durack arrived in 1853 escaping the effects of the ‘potato famine’ in Ireland. The Durack wives suffered supreme hardships; taken by their men in horse and cart to the far reaches of western QLD (ultimately Thylungra Station) on the Northern Territory border to set up house next to a dry creek bed. In God-forsaken country hundreds of miles from real habitation, losing numerous children there and along the way, these women literally built lives from dirt, a few provisions and nothing else.

It was that or perish. Stoicism and the determination of pioneering women is what Australia was built upon; many of the Durack women, in particular, must have often wondered how a ‘potato famine’ could possibly be worse.

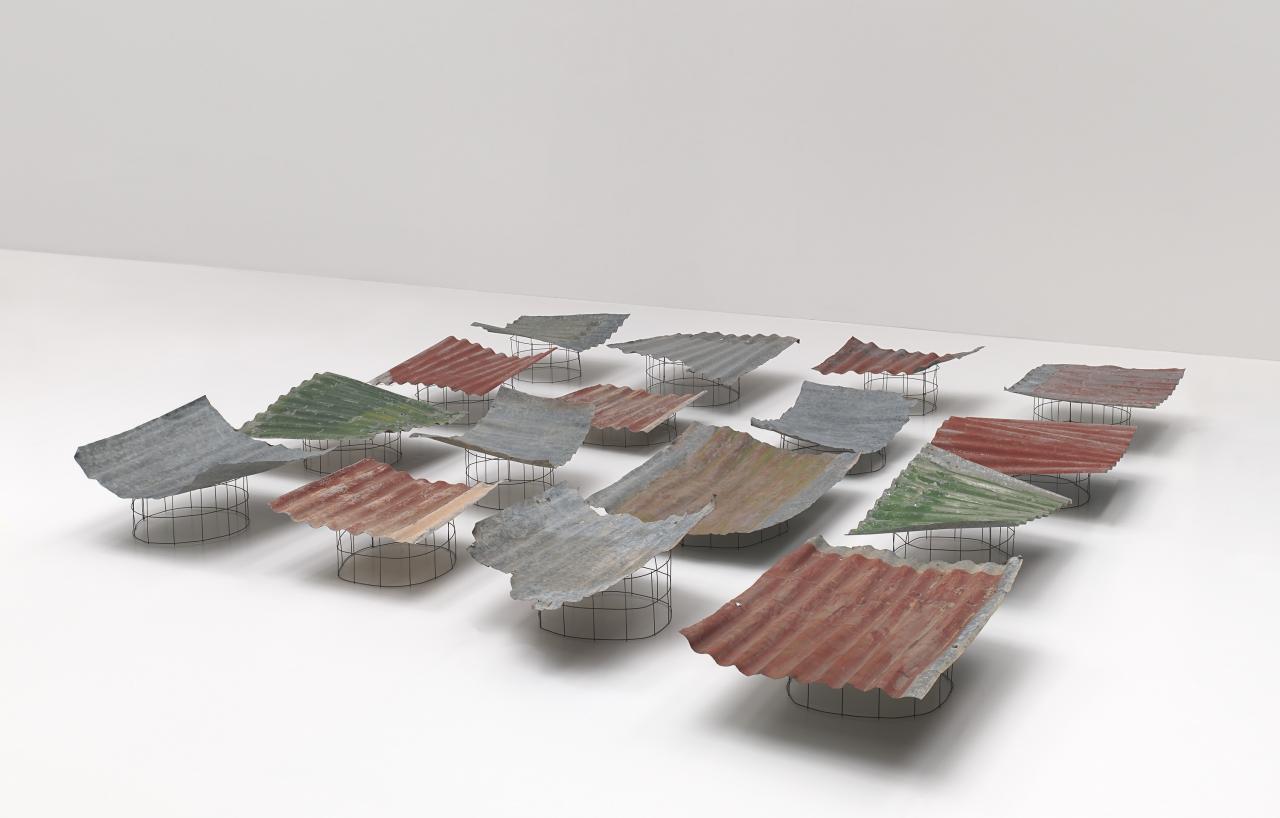

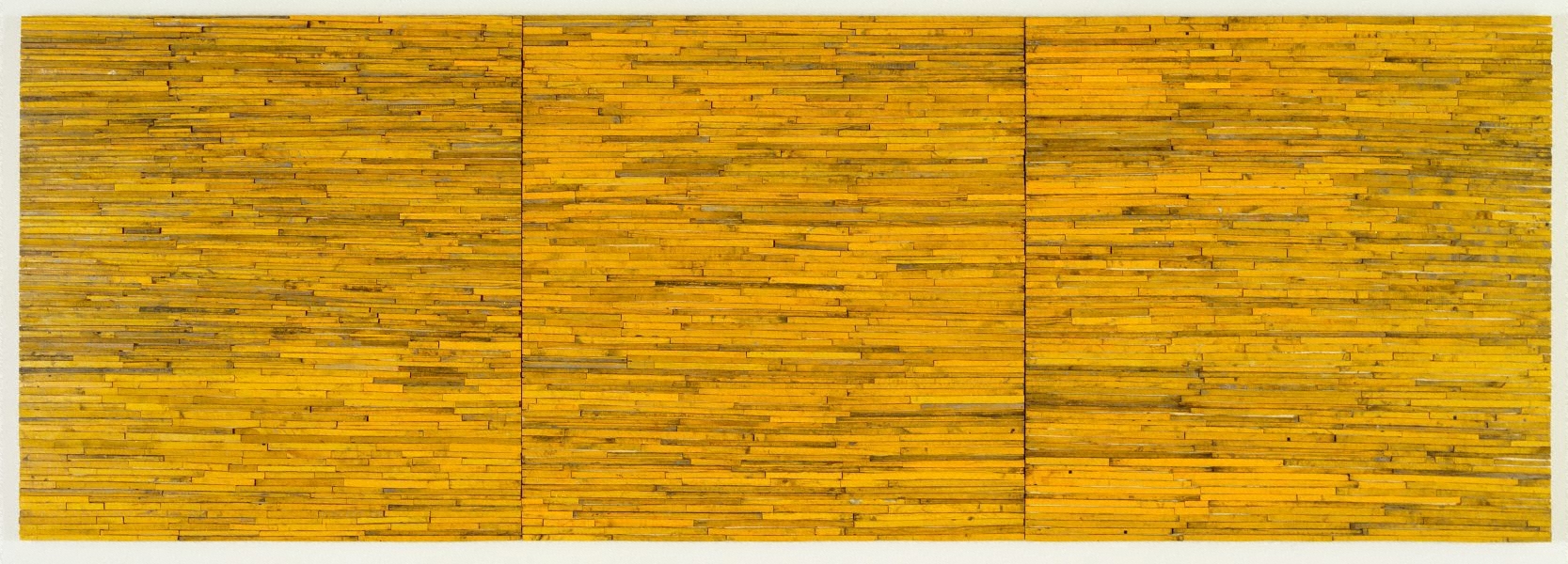

While these two works symbolise stoicism, endurance and resourcefulness (both actually and metaphorically) they are also symbolic of the growth of Australian towns. Like newspapers hidden under lino or preserving jars and long-necked beer bottles stacked up in the shed, corrugated iron in the outback is found in every town in every form of building – and in every junkyard. It came sized and in lengths that could be easily stacked and moved, and it was relatively easy to put up. On one hand, the aptly titled Inland Sea speaks directly to Australia’s early history in the use of corrugated iron in the formation of outback towns and properties, and on the other it resembles ‘waves’ with a multitude of associated inferences located in the experiences of the viewer.

Consciously or not Inland Sea reminds Australians that pioneering explorers went in search of the “inland sea”.

Australia is marked by two major obsessions – solving the mystery of the western river system and searching for the mythical inland sea. Over a thirty year period, surveyors George Evans, John Oxley, Charles Sturt and Thomas Mitchell were employed to make a series of expeditions into the interior of the continent.

By association, the work also speaks to the great difficulties the early explorers encountered trekking into the middle of Australia to map the country, in search of pasture and river systems. Many lost their lives in the process such as Burke and Wills and others in their party.

Linked to exploring central Australia in the 19th century, is the concept of the mirage. It is hard to look at Inland Sea without thinking of the mirage in Australian mythology; it is said that mirages sent people mad in the desert in the quest for water. It is easy to make the connection – imagine Inland Sea as a mirage would look in the distance – rippling waves of light being mistaken for water. Contiguously, that same symbolism reminds us of the opposite, in that inland sea “implies water” and most of inland Australia is characterised by an absence of water. The sheets of iron as hard, unforgiving, and as desolate as the paddocks become after years of drought.

__________________________

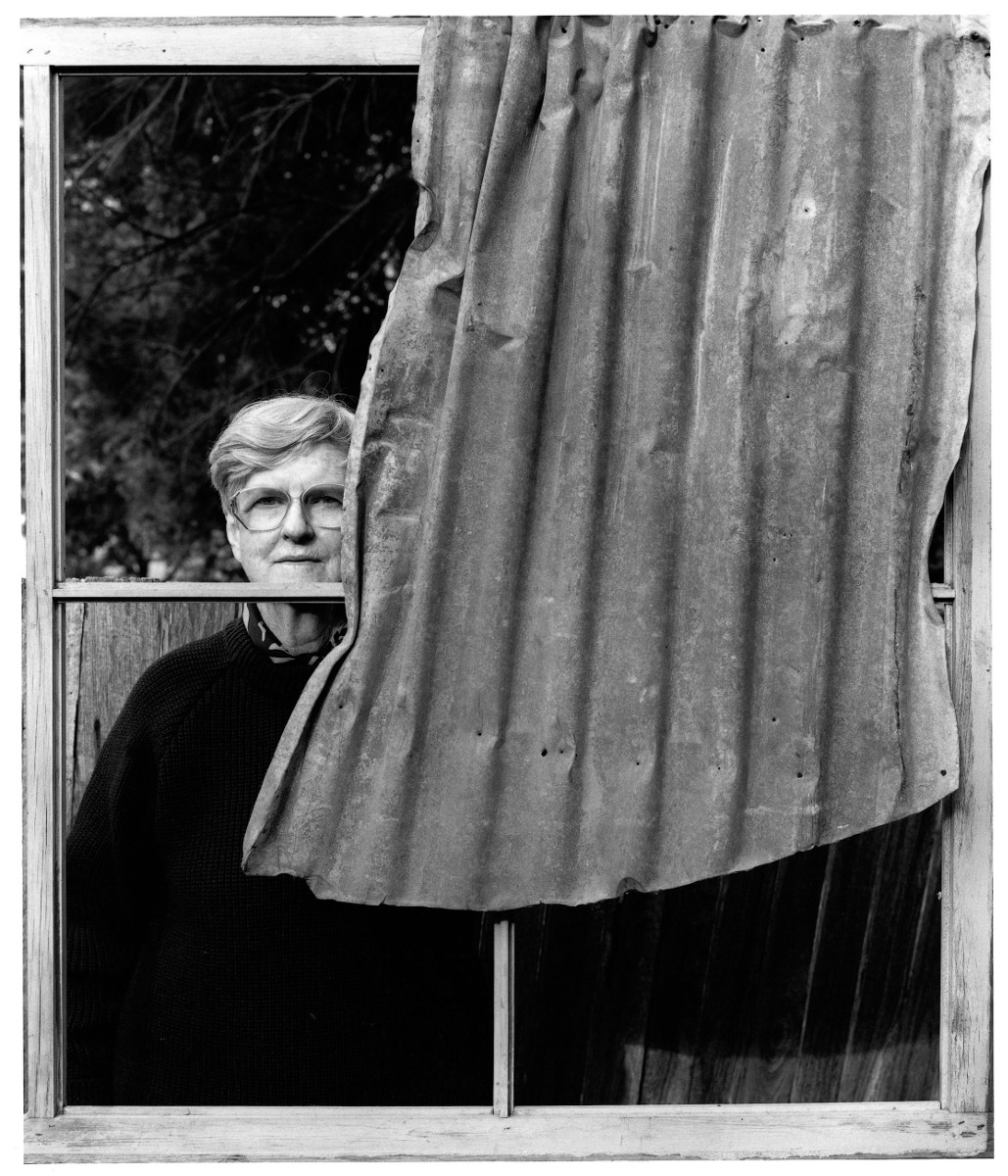

Pink Window can be read or interpreted similarly; a weathered piece of found corrugated iron serves as a flapping curtain. Alternatively, a breeze-filled curtain has solidified – these are obvious references. In one way, the work symbolises Gascoigne’s processing of her past life with her present life in Mt Stromlo – she looks out onto another world – a vast alien world which she comes to identify with: both surrounding and steeping herself within.

Deeper explanations can be applied – the landscape looked in on Gascoigne and eventually, it drew her out enveloped her and she became part of its mystery – a mystery that could never be fully articulated. Like truth, it refused to be pinned down to a single or simple explanation or interpretation. It is a process of understanding and Gascoigne’s innumerable works are testimony to that fact. The window in general terms is a symbol of hopes, dreams, obsessions and stoicism in a not dissimilar way to that of the telephone prior to the impact of social media – the same type of iconographic references can be applied.

When reading Martha Caldwell Cox’s account of taking up land with her husband in the far reaches of QLD in the 19th century, the concept of “window” as an emblem of loneliness is palpable. The need for female company was so great that often a year, sometimes years would go by before she (and many like her) saw another woman and as such depression was a significant problem to compound typical day-to-day problems of survival; such as scurvy for instance.

The window of the home is also a reminder of domestic enclosure, a demarcation between life as a wife, mother, and domestic inside while outside represented a release from that persona: Rosalie Gascoigne once described the exterior as ‘all air, all light, all space and all understatement’; the exterior came to represent her creative self.

The space and freedom she saw in the country around her provided not only a great contrast to the restrictions of her life in Auckland but also an escape from the tedious domesticity of life as a 1950s housewife in a very isolated environment.

The window has been used similarly throughout the history of art by innumerable artists to symbolise female loneliness, isolation, depression or the irrevocable passing of time. The Pre-Raphaelite John Everett Millais’s Mariana (1851), inspired by a Tennyson poem of the same title is well known for the female subject standing before a window.

When it was first exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1851 this picture was accompanied by the following lines from Tennyson’s Mariana (1830):

She only said, ‘My life is dreary,

He cometh not,’ she said;

She said, ‘I am aweary, aweary,

I would that I were dead!’

Other prominent artists like Vilhelm Hammershoi, Johannes Vermeer and Caspar David Friedrich, David Hockney and many more have employed the window symbolically.

What we see in Gascoigne’s work is an Australian archetype in a manner that can be compared to Dorothea Mackellar’s My Country. What Dorothea Mackellar did for our view of Australia in verse Gascoigne did for our view of Australia in art via the found object.

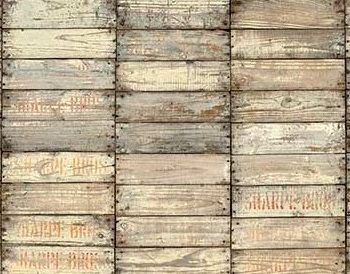

Gascoigne sourced either natural or man-made objects that told their own story of Australian life and conscripted them to tell a unique and personal story of her own relationship with Australia. These stories often spoke of her identification with the landscape directly in and around Canberra such as Monaro while others such as Metropolis are ground in more universal themes of existence.

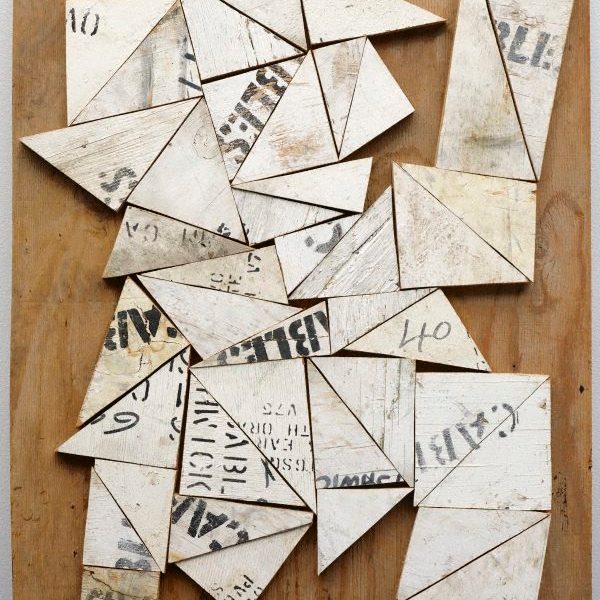

Rosalie Gascoigne’s work is in the collection of many Australian and NZ public galleries. Gascoigne is known as an assemblage artist (TATE: Assemblage is art that is made by assembling disparate elements – often everyday objects – scavenged by the artist or bought specially)

*Featured image: Pineapple Piece 6, 1985, Assemblage of found wooden elements, (h)17 x (w)28.6 x (d)4.7cm (6.6″ x 11.2″ x 1.8″) (Collection National Gallery Australia)

Art Gallery NSW (AGNSW)

National Gallery of Australia (NGA)

National Gallery Victoria (NGV)

Auckland Art Gallery / Toi o Tamaki

Te Papa, Wellington NZ