Serpentine Galleries London

Until 19 May 2019

Art exhibition “Emma Kunz – Visionary Drawings”

The Serpentine presents the first UK solo exhibition by the late Swiss visionary artist, healer and researcher Emma Kunz (1892 – 1963) that features over 40 of her rarely seen drawings.

Critique of Emma Kunz ‘visionary drawings’: some thoughts on how to interpret them.

I confess to being dazzled by the intricacy, pattern and ‘obsessive’ linear elements intrinsic to Emma Kunz’s work.

I am less interested in them as conduits from corporeal to spiritual states. However, I agree art has the power to elicit a spiritual response, and that response can be harnessed to make or enact changes to an individual’s life.

It is however, impossible to look at the more labyrinthine works and not acknowledge a ‘spiritual dimension’ in that they indicate a mind capable of making complex connections.

The immensity, beauty and complexity of the finished works would be sufficient to transform a purely intellectural process into one of emotional transcendance.

Contiguous with these thoughts, is the notion of binary opposition. There is no doubting the function of binary opposites; simply put, if we take the concept of ‘rational’, the binary opposite is ‘irrational’. Binary opposites form two sides of the same coin, and all binary opposites (good/bad; dark/light etc) operate similarly. We cannot understand one concept without also having an awareness of its corresponding opposite. In fact no one concept is ‘conceivable’ without the other; they are irrevocably united semantically.

It is possible that Kunz rational, ordered ‘energy fields’ were deciphered in the more ‘irrational’ area of the emotions. It is contended that, Kunz sought ‘diagnoses for her patients who would visit her seeking help for physical and mental ailments’. The very intricacy of the drawings could be interpreted as a pipeline for ‘emotional release’ when investigated objectively. This could be a revealing experience for Kunz patients; life’s ‘big picture’ revealed in the web of single linear markings. Extrapolating, the ‘whole of one’s life’ can be mapped in the minutiae of individual events.

The ‘whole of life’ is made up of complex inter-connections, paths, choices, journeys and communications: the works themselves exemplify these concepts.

Human beings are one-off, peculiar creations of infinite complexity and beauty. No less now than it was in Kunz’s day, as individuals we can investigate and channel that personal complexity and singularity to more cathartic and positive ends.

As Kunz’s life experience appears to demonstrate, some of us need help to achieve positive, emotionally beneficial results from our unique experiences. Perhaps for the artist, both the complex forms and associated psychological insights gleaned on behalf of patients, increased exponentially as the final forms took shape.

Similarly, American artist Agnes Martin had a preoccupation with abstract geometric art as well as a preoccupation with happiness. Martin believed her best work came from a well of personal happiness, which she discussed extensively. “The goal of life is happiness and to respond to life as though it were perfect is the way to happiness,” she explained in a 1987 lecture at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture. “It is also the way to positive artwork.”

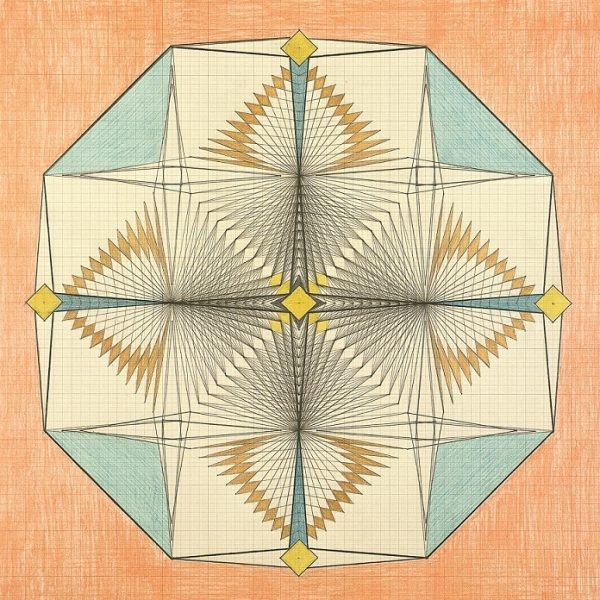

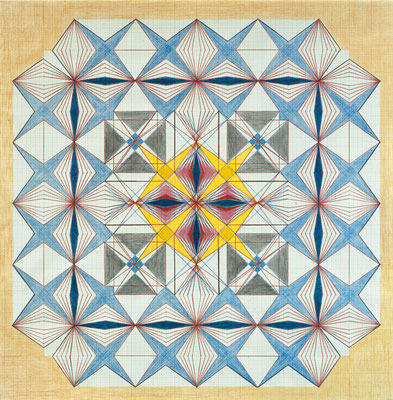

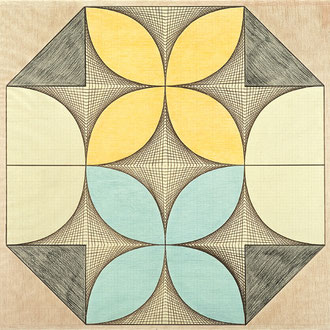

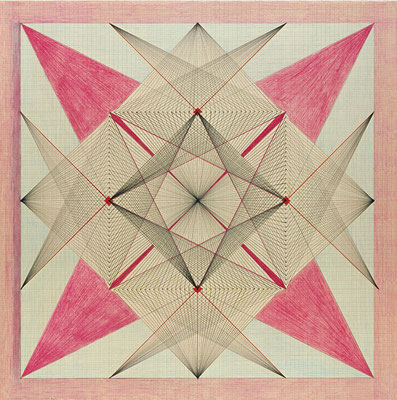

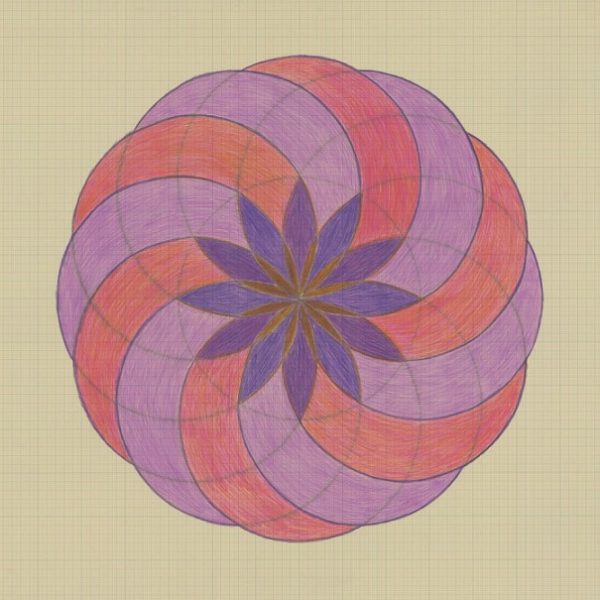

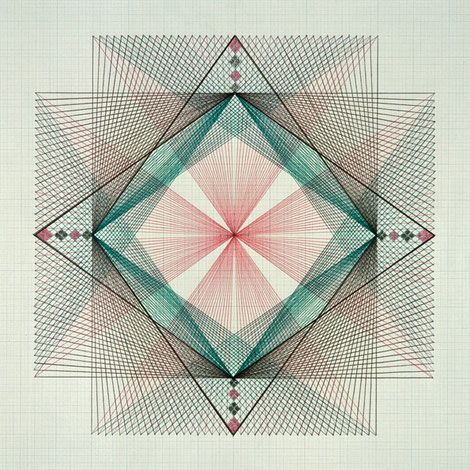

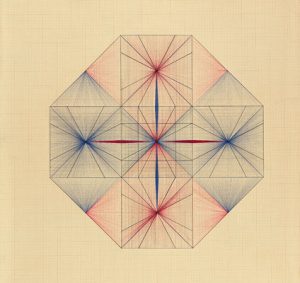

From a compact centre or centres the more ‘abstract’ linear compositions move towards the periphery by increments; potentially ‘never-ending’ patterns, give the impression of a universe infinite. Superficially, the works seem to evolve from intimate points to indicate a vast unfolding and unknown world seen from a singular point of view. These refined works (especially ‘141’ & ‘115’) are characterised by an almost obsessive desire for symmetry and geometric pattern; like much of Briget Riley’s work, they border on the ‘optical illusion’ of movement. Tate gallery ‘Due to the number and overlapping of geometric and linear elements, the highly detailed works appear to shift and move within their borders.’

The detailed fascination with line, symmetry and compass-like points means works such as ‘141’ appear at once to oscillate within the borders while exhibiting three dimensional qualities.

Triangles spark and pulse electrically across our vision.

Although the number of civic rules and regulations that govern our lives now were not present to the same extent in the late 19th and early 20th century, generally, we are creatures of habit. We repeat what works for us psychologically and physically. Thus, in many essential ways our lives are governed by pattern and ritual. Two things, it is interesting that Emma Kunz predicted her drawings were destined for the 21st Century. In the present day, it could be argued that we are controlled by civic, corporate and economic rules, yet creative pursuits have the ability to release us from conformity. Secondly, Kunz seems to hint at greater enlightenment and understanding by a 21st century audience. A contestable value judgement then and now.

Of particular interest additionally, is the concept of ‘figure and ground’. When the figure and ground of a composition are clear, the relationship is stable; the figure element receives more attention and is better remembered than the ground. In unstable figure-ground relationships, the relationship is ambiguous and can be interpreted in different ways; the interpretation of elements alternates between figure and ground.

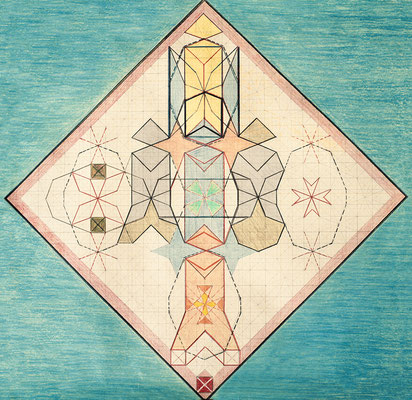

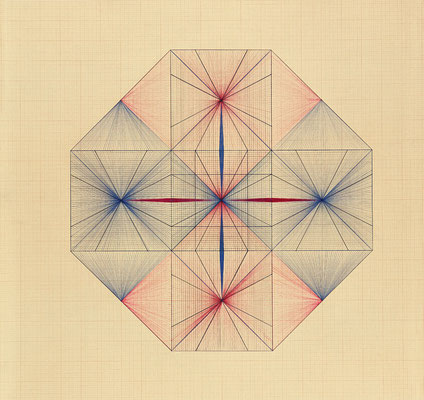

In theworks ‘141’, ‘115’, ‘008’ and ? the ground is essential to or integral to the work; for the uninitiated the ‘ground’ is the ‘paper’ on which the markings are made, or the surface of the paper.

Looking at the accompanying octagonal.

Two deeper pink horizontal rhombus appear to have ‘severed the surface’ of the paper, enabling the viewer to imagine another dimension beyond the picture plane. In this way the artist connects the physical art object with metaphysical and psychological worlds.

Two deeper pink horizontal rhombus appear to have ‘severed the surface’ of the paper, enabling the viewer to imagine another dimension beyond the picture plane. In this way the artist connects the physical art object with metaphysical and psychological worlds.

This is especially relevant when Kunz’s raison d’être combines the physical object with her research into spiritualism and healing.

The compelling and detailed drawings promote and reflect a combined love of science, mathematics and art with a basis in order and pattern. Kunz was able to harness these attributes to reflect a unique and stunning vision.

Shape and form expressed as measurement, rhythm, symbol and transformation of figure and principle.

These are just a few of the immediate impressions of Emma Kunz’s work and are by no means exhaustive, there is a great deal more that could be said.

EMMA KUNZ CENTRE

The estate of Emma Kunz comprises about 500 pictures. Every month we offer you the opportunity to immerse yourself in a new image. No written statements were made by Emma Kunz.

Emma Kunz recorded her knowledge in large-format drawings on graph paper, and their significance extends far beyond their aesthetic beauty.

The works are visible testimony of her research, represented by strictly geometric drawings on graph paper with pencil, coloured pencil and oil pastels, whose content, among other things, provides answers to her questions about life and its spiritual implications.

According to Emma Kunz, her paintings are destined for the 21st century, and during that time her pictures will be decoded.

In the past, Emma Kunz’s work has been shown alongside

In the past, Emma Kunz’s work has been shown alongside