Until 24 Jun 2018

AGNSW (Art Gallery New South Wales): https://goo.gl/VQSKn5

The lady and the unicorn series

Only the third time The lady and the unicorn tapestry series has left France in 500 years, this is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to see these magnificent artworks in Sydney.

Revered as a French national treasure The lady and the unicorn tapestry series, often referred to as the ‘Mona Lisa of the Middle Ages’, will be making its exclusive appearance in Sydney at the Art Gallery of NSW through a generous and exceptional loan from the collection of the Musée de Cluny – Musée national du Moyen Âge in Paris.

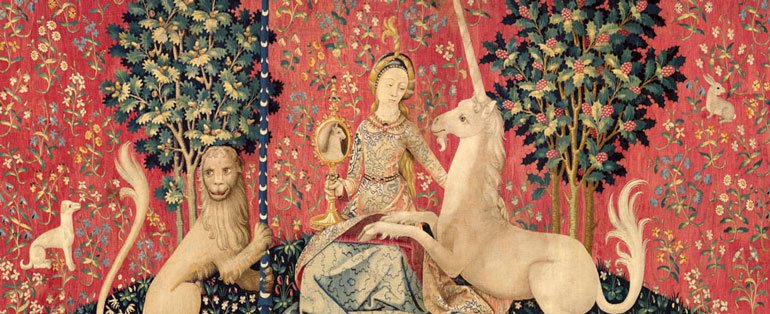

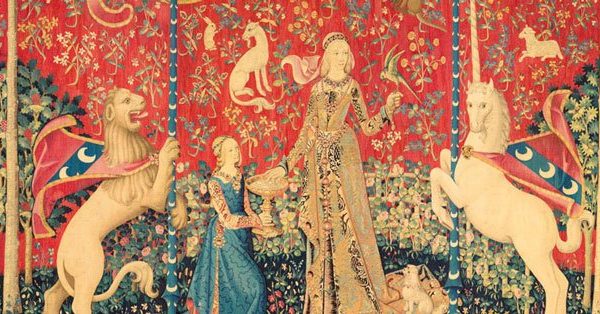

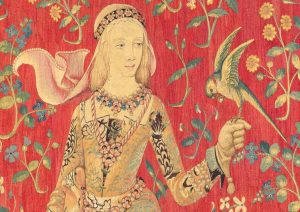

Designed in Paris about 1500, the tapestries are considered to be some of the greatest surviving masterpieces of medieval European art. They depict a lady flanked by a lion and a unicorn, surrounded by an enchanting world of animals, trees and flowers. One of the most intriguing aspects of these six large-scale artworks is the mystery of their origin and meaning. For whom were these masterpieces made? What do they symbolise? What stories do they tell?

Often interpreted as a vivid meditation on earthly pleasures and courtly love, the tapestries showcase the sublime skill of medieval artisans. They can also be viewed as an allegory of the five senses – sight, hearing, taste, touch and smell – as well as a sixth sense – heart or will – represented by the phrase ‘mon seul désir’ or ‘my sole desire’.

An engaging program of events and activities, including film, digital and tactile experiences for all ages, will help unravel this centuries-old mystery and illuminate the beauty and intricacy of these enigmatic masterpieces.

This exhibition is made possible with the support of the NSW Government through its tourism and major events agency, Destination NSW.

THE CONVERSATION

THE LADY AND THE UNICORN ESSAY: Mark De Vitis, Lecturer in Art History , University of Sydney: https://goo.gl/NDRFo6

The arrival of The Lady and the Unicorn tapestry cycle at the Art Gallery of New South Wales from February 10 presents a rare opportunity to see a work of art revered by specialists and enthusiasts alike. It has been called everything from the “Mona Lisa of the Middle Ages”, to “a national treasure of France”. Comprising six individual pieces and made around the year 1500, tapestries of such quality are rare, and few examples survive.

Materially, they are breathtaking. Their elaborate millefleur (“thousand flowers”) backgrounds form hypnotic patterns. The sumptuous stuff from which they are woven – wool and silk, dyed with rich, natural dyes – insulate the beholder (literally part of their original function.) They muffle sound, creating an atmosphere of quiet mediation. The air is stilled, and light is enriched by their surfaces, generating a transcendental aura that draws the beholder into their complex internal universe.

The cycle first came to public attention in the middle of the 19th century, discovered languishing in the decaying château de Boussac, located in central France. Gnawed at by rats and threatened by the dank conditions, they were rescued by the musée de Cluny in 1882, bought for the princely sum of 25,500 francs.

The amount paid by the Cluny museum would have represented just a fraction of the original cost of their production, however. Tapestries of such quality would have commanded more than the annual income of all but the richest members of the nobility. More than a battleship. Far more than Michelangelo was paid to paint the Sistine ceiling.

The amount paid by the Cluny museum would have represented just a fraction of the original cost of their production, however. Tapestries of such quality would have commanded more than the annual income of all but the richest members of the nobility. More than a battleship. Far more than Michelangelo was paid to paint the Sistine ceiling.

Unsurprisingly then, the patron of the cycle came from a noble family with close ties to the French monarchy – the Le Viste. This is made clear from the heraldic symbols shown in the tapestries themselves. They were most likely designed by the “Master of Anne of Brittany” (so called because he designed a book of hours for the French queen, Anne of Brittany), a preeminent artist of the day.

Though we might fixate on the artist who designed the composition, tapestries were made collaboratively, and the Lady and the Unicorn cycle was probably woven in the Southern Netherlands, not France, for the standard of weaving was higher there.

Given the effort and investment required to produce them, it is little surprise that the subject of the tapestries is complex – something worthy of more than a mere glance. The meaning of the cycle has been much debated. Experts now (generally) agree that they present a meditation on earthly pleasures and courtly culture, offered through an allegory of the senses.

Five of the tapestries each depict one of the senses (Touch, Taste, Smell, Hearing and Sight.) Each shows a woman (the “Lady” of the title) performing some action intended to exemplify the sense in question. In “Smell” the Lady is presented with a dish of carnations. In ‘Hearing’ she plays at an organ. In “Sight”, she holds a mirror, which reflects the image of a unicorn that rests in her lap.

Each of these gestures is presented with much charm and grace, conveyed through gently curving lines that show no sharp transitions. Yet, all is not as peaceful as it may seem. For there is a sixth tapestry. Though it is clear that all six are meant to form a unit, as each displays the same basic format and figures, the sixth work breaks the pattern of the other five.

Here, the Lady is depicted returning jewels (worn in the other tapestries) to a casket. She stands before a tent emblazoned with the words Mon Seul Désir (“my only desire”.) Her action does not connect with sensory or empirical experience, as with the other five, but is instead driven by some alternate force – cognition, moral reasoning, or emotion.

A sixth sense is represented in this sixth tapestry, which presents a further way of knowing the world. This sense seems to have not one, but multiple dimensions. Intellectually, it may be thought of as common sense, or “internal” sense. Morally, it may be understood to encapsulate neo-platonic philosophy’s emphasis on the soul as the source of beauty (read the “good”.) In terms of courtly rhetoric, the sixth sense may be thought of as the heart, the source of courtly love and the home of complex or competing forces – free will, carnal passion, desire.

A sixth sense is represented in this sixth tapestry, which presents a further way of knowing the world. This sense seems to have not one, but multiple dimensions. Intellectually, it may be thought of as common sense, or “internal” sense. Morally, it may be understood to encapsulate neo-platonic philosophy’s emphasis on the soul as the source of beauty (read the “good”.) In terms of courtly rhetoric, the sixth sense may be thought of as the heart, the source of courtly love and the home of complex or competing forces – free will, carnal passion, desire.

It is this sixth sense that leads the Lady to return her jewels to her casket. The gesture may be read as a sign of her virtue, an expression of the dominance of her reason over the physical sensations she experiences in the other tapestries, or, of the will as the centre of being. In this interpretation, the phrase Mon Seul Désir could be read not as “my sole desire” but “by my own free will”.

A sixth sense

A sixth sense is represented in this sixth tapestry, which presents a further way of knowing the world. This sense seems to have not one, but multiple dimensions. Intellectually, it may be thought of as common sense, or “internal” sense. Morally, it may be understood to encapsulate neo-platonic philosophy’s emphasis on the soul as the source of beauty (read the “good”.) In terms of courtly rhetoric, the sixth sense may be thought of as the heart, the source of courtly love and the home of complex or competing forces – free will, carnal passion, desire.

It is this sixth sense that leads the Lady to return her jewels to her casket. The gesture may be read as a sign of her virtue, an expression of the dominance of her reason over the physical sensations she experiences in the other tapestries, or, of the will as the centre of being. In this interpretation, the phrase Mon Seul Désir could be read not as “my sole desire” but “by my own free will”.

This multi-layered approach to interpreting the tapestries is echoed in other, localised features. For instance, the unicorn, which is represented in all six tapestries, embodies various, overlapping meanings. Unicorns were common heraldic animals, and frequently appear in courtly literature. Since the second century they were understood to represent chastity or purity. Certainly, this meaning connects with the reading of the Mon Seul Désir tapestry offered above.

The unicorn also acts as a canting emblem – that is, a pun on the name of the patron. Le Viste may be pronounced more like “Le Vite” in French, meaning fast. Fast, like a unicorn.

The inclusion of the unicorn also contributes to the sense that the tapestries intentionally encourage a viewer to evaluate types of knowledge or understanding. Representations of unicorns (both past and present, it could be argued) raise questions regarding how we come to know, and how empirical knowledge exists alongside tradition, culture, imagination, and creative expression.

More than a series of objects with remarkable aesthetic, historical and economic significance, the Lady and The Unicorn tapestries offer an opportunity to confront how different forms of understanding and experience overlap to form beliefs, shape perspectives, and precipitate action.

Image: www.biography.com

At around the time the Lady and the Unicorn tapestry series was thought to have been produced, Hieronymus Bosch produced The Garden of Earthly Delights – a secular triptych about God’s creation of the world, of man (and his attendant free will, which sets him apart from animals in that way only) and the consequences of that free will. Sally Hickson discusses the work below and it struck me as interesting in light of the Lady and the Unicorn tapestries and what they depict when compared to Bosch’s triptych and both the religious and secular implications.

Hieronymus Bosch: The Garden of Earthly Delights, c1480 – 1505

Hieronymus Bosch, born Jeroen Anthonissen van Aken was born Jheronimus (or Jeroen) van Aken (meaning “from Aachen”). He signed a number of his paintings as Bosch (pronounced Boss in Dutch). The name derives from his birthplace, ‘s-Hertogenbosch, which is commonly called “Den Bosch”.

“Little is known of Bosch’s life or training. He left behind no letters or diaries, and what has been identified has been taken from brief references to him in the municipal records of ‘s-Hertogenbosch, and in the account books of the local order of the Brotherhood of Our Lady. Nothing is known of his personality or his thoughts on the meaning of his art. Bosch’s date of birth has not been determined with certainty. It is estimated at c. 1450 on the basis of a hand drawn portrait (which may be a self-portrait) made shortly before his death in 1516. The drawing shows the artist at an advanced age, probably in his late sixties.

Bosch was born and lived all his life in and near ‘s-Hertogenbosch, the capital of the Dutch province of Brabant. His grandfather, Jan van Aken (died 1454), was a painter and is first mentioned in the records in 1430. It is known that Jan had five sons, four of whom were also painters. Bosch’s father, Anthonius van Aken (died c. 1478) acted as artistic adviser to the Brotherhood of Our Lady. It is generally assumed that either Bosch’s father or one of his uncles taught the artist to paint, however none of their works survive. Bosch first appears in the municipal record in 1474, when he is named along with two brothers and a sister.

Hertogenbosch was a flourishing city in fifteenth century Brabant, in the south of the present-day Netherlands. In 1463, 4,000 houses in the town were destroyed by a catastrophic fire, which the then (approximately) 13-year-old Bosch may have witnessed. He became a popular painter in his lifetime and often received commissions from abroad. In 1488 he joined the highly respected Brotherhood of Our Lady, an arch-conservative religious group of some 40 influential citizens of ‘s-Hertogenbosch, and 7,000 ‘outer-members’ from around Europe.

Some time between 1479 and 1481, Bosch married Aleyt Goyaerts van den Meerveen, who was a few years older than the artist. The couple moved to the nearby town of Oirschot, where his wife had inherited a house and land, from her wealthy family.

An entry in the accounts of the Brotherhood of Our Lady records Bosch’s death in 1516. A funeral mass served in his memory was held in the church of Saint John on 9th August of that year.”

KHAN ACADEMY: Dr. Sally Hickson / Associate Professor art history University of Guelph, Ontario, Canada. https://goo.gl/HBvt2L

Deciphering the indecipherable: Important aspects of the essay below, for the entire essay click on link above:

The Garden of Earthly Delights “… is a creation and damnation triptych, starting with Adam and Eve and ending with a highly imaginative through-the-looking glass kind of Hell. No one really knows why Bosch imagined the world in this particular way.

Here’s what I think. What concerned Bosch, in his triptych of creation, human futility and damnation (the Garden of Earthly Delights is a modern misnomer for the work), was the essentially comic ephemerality of human life.

It should be pointed out that this work, like Bosch’s Hay Wain triptych (also framed by a creation and damnation scene), is a triptych only in form; neither depict the conventional arrangement of a tripartite altarpiece because their center panels do not include religious figures or even religious scenes. What Bosch seems to have invented is an entirely new form of secular triptych, one that functioned kind of like a Renaissance home theatre package for wealthy patrons.

The introduction of woman to man, in this setting, is clearly intended to highlight not only God’s creativity but human procreative capacity. In the hierarchy of God’s handiwork, Adam and Eve represent his most daring achievement, as though after he’d made everything else he thought he needed to leave a signature on the world in which he could recognize himself. It’s a matter of conjecture, when one proceeds to the central panel, as to whether Bosch is saying that the creation of man, on whom God conferred free will, might have been a divine mistake.

Given Bosch’s emphasis on nude figures, some of which are engaged in amorous activities —although none in flagrante—this central scene has often been interpreted as a warning against lust, particularly in conjunction with the third panel, depicting Hell (the Spanish Hapsburgs, in fact, referred to the work as “La Lujuria” — lust). I wonder though. Bosch’s depiction of humans cavorting in the elemental world of God’s creation, seems, to me, less inculpatory than simply a commentary on the fact that there’s little to differentiate man from animals from plants.

Bosch saves the best for last. Earlier visions of Hell, if indeed that’s what Bosch intended here, are pretty tame in comparison to this. Against a backdrop of blackness, prison-like city walls are etched in inky silhouette against areas of flame and everywhere human bodies huddle in groups, amass in armies or are subject to strange tortures at the hands of oddly-clad executioners and animal-demons.

Overall, there is a marked emphasis on musical instruments as symbols of evil distraction, the siren call of self-indulgence, and the large ears, which scuttle along the ground although pierced with a knife, are a powerful allusion to the deceptive lure of the senses. In fact, many of the symbols and the tortures here are pretty standard in the catalogue of the Seven Deadly Sins, in which our senses deceive our thoughts into self-indulgent over-consumption.

It seems to me that this is the question the whole triptych asks—whether God, having made the world and having conferred on man both the blessing and the curse of free will, would destroy all of his creation in the face of human failing. This is the fundamental connection between these inner panels and the destructive flood depicted on the outer wings. Bosch’s lesson, if there is one, seems to be that we can choose good over evil or we can be swept away. Man proposes, God disposes.